What follows is a lengthy portion from Josh Hayes over at REVELANT:

As A.W. Tozer said, “What comes into our minds when we think about God is the most important thing about us.” Therefore, how we think about the Trinity (i.e., the Christian view of God) is of highest importance. So, here are three trinitarian basics to keep in mind when considering this weighty, mysterious and often-misunderstood concept:

1. God is one in essence and three in person.

Without reciting the first several centuries of church history, we can, in a nutshell, say that after much careful reflection and discussion, Christians came to confess that God eternally exists as three personal subjects—Father, Son and Holy Spirit—who possess one undivided nature (also sometimes, essence or substance). Each person is fully and equally God because each enjoys the attributes that qualify as divine (i.e., self-existence, eternity, omnipresence, etc.).

The doctrine of the Trinity is not irrational (against reason), though it is supra-rational (beyond reason).

We use the terminology, which today seems really odd, “essence” and “person,” while not found in Scripture, so that Christians can affirm with Scripture that only one God exists (Deuteronomy 6:4; James 2:19), while also acknowledging that Scripture in various places identifies Father, Son and Holy Spirit each as God (e.g., 1 Cor. 8:4-6; John 1:1-3,14; 20:28; Heb. 1:1-3,8, 10; Acts 5:3-4; 28:25-26; 1 Cor. 2:10-11).

The doctrine of the Trinity is not irrational (against reason), though it is supra-rational (beyond reason).

So, instead of speaking of one God with three “aspects,” as Martin suggests, it is more accurate and helpful to use the word “persons” in order to avoid intimating that God is somehow made of pieces or parts.

2. Christians distinguish the three persons of the Trinity by their respective personal properties and coinciding relationships.

As the Church reflected upon what the Bible teaches about the one-in-three God during its first several centuries, theologians and pastors came to adopt the terms of “unbegotten,” “begotten” and “proceeding” to speak respectively of each person: The Father is unbegotten; the Son is eternally begotten by the Father; and the Spirit eternally proceeds from the Father and the Son.

In other words, one is not the loneliest number, because for God the one never exists without the three.

Love requires relationships, and so the doctrine of the Trinity shows us how God is loving even before His creatures existed.

There has never been a point when God was not a Father (and a Son). And there has never been a time when the Spirit did not exist as the one who unites the Father and the Son in active abiding love. The Trinity isn’t conjoined triplets with identical personalities; the three really are eternally distinct (while one in essence) and participate in relationship with one another.

They don’t just become different in the parts they each play in the drama of God’s story of redemption.

The doctrine of the Trinity, gives content and structure to the statement “God is love” (1 John 4:8,16), for love requires more than one person. Love requires relationships, and so the doctrine of the Trinity shows us how God is loving even before His creatures existed.

The terms “unbegotten,” “begotten” and “proceeding” don’t refer to properties found in God’s unified nature but to the persons and the relationships that exist among them eternally.

To Martin’s childhood question “So he’s his own father and own son?” we should respond, “No, God the Father is the father of God the Son, according to their eternal relationship and respective personhood, yet they are mysteriously one God with respect to their essence.”

3. The Trinity’s actions in history reveal who the Trinity is in eternity.

The third truth serves as the basis for how we know the first two basics. God acts in accordance with who He is; so, any time He reveals Himself, it’s a trinitarian revelation.

We know what is true about God’s relationships in Himself before creation (e.g., the Father eternally loves the Son in the Spirit) because of the relationships we see among the Father, Son and Holy Spirit in creation (e.g., the Father sends, the Son comes, and the Spirit completes). There is a “fittingness” between their roles in history and who they are in the Godhead from eternity.

This is the distinction that Christian theologians make between what’s called the “ontological Trinity” (God as He exists apart from creation) and the “economic Trinity” (God as He is known to us in creation). Confused? Theologian Fred Sanders might be of some help here:

God has given form and order to the history of salvation because he intends not only to save us through it but also to reveal himself through it. The economy is shaped by God’s intention to communicate his identity and character. If the history of salvation is also the way God shows us who he is and what he is like, then it makes sense that it would be a history with a clear and distinct shape … The center of the economy of salvation is the nexus where the Son and the Holy Spirit are sent by the Father to accomplish reconciliation. (“The Deep Things of God: How the Trinity Changes Everything,” 133)

Because God’s actions tell us something about who He is, the economic Trinity reflects the ontological Trinity. The roles of Father, Son and Holy Spirit in history are more than God doing different jobs and using different titles. It is God’s way of saying to the world, “This is who I am!”

This all can seem complicated and technical, but the point is that God really does reveal Himself to us; He isn’t putting on masks randomly or arbitrarily.

And to some, the above might seem trivial. But no Christian should think like this, however, because the gospel itself is trinitarian in both its shape (Rom. 1:1-4; Gal. 4:4-7) and its goal (John 1:18; 17:3; cf. Matt. 11:27; Heb. 1:1-2).

The same truth holds for Martin as it does for us: “What comes into our minds when we think about God is the most important thing about us.”

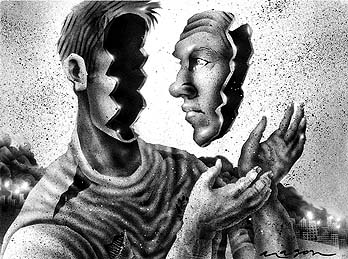

Some people dwell so much on their sinfulness that they find themselves constantly bombarding their status with doubt. Am I really a Christian? Am I worthy? These questions are not atypical of those who grow up in environments where internalized Christianity is emphasized. There is a healthy form of self-examination and Paul informs Pastors (II Corinthians 13:5) to encourage parishioners to examine themselves. At the same time, there is a difference between self-examination and introspection that is not often considered.

Some people dwell so much on their sinfulness that they find themselves constantly bombarding their status with doubt. Am I really a Christian? Am I worthy? These questions are not atypical of those who grow up in environments where internalized Christianity is emphasized. There is a healthy form of self-examination and Paul informs Pastors (II Corinthians 13:5) to encourage parishioners to examine themselves. At the same time, there is a difference between self-examination and introspection that is not often considered.