The Nicene Creed, A Friendly Introduction

Everyone has a creed! Some creeds are created after their own image, and others reflect the broader faith of our fathers!

I want to offer my readers a friendly introduction to the Nicene Creed. By friendly, I mean I will not deal with the textual issues, the filioque[1] clause, or some historical debates.

The stated presupposition of this essay is that every Christian Church must be a creedal Church. Those who question the authority of the Creed do not understand the function of authority in the history of the Church and are most likely to treat the Bible rigidly and mechanistically. They open themselves to a myriad of heresies.

The Church and her dogma were not a creation of Rome, but she has always existed, even when it was most unfaithful. The Church, founded on the blood of the martyrs and especially on the blood of Christ, was called to be a light to the world. But you need a mission statement if you will be a light to the world. The Church worked very hard to form this mission statement.

The first official mission statement of the Church was the Nicene Creed.

The Role of the Creed

The Creed was ecumenical, encompassing every dimension of Christendom. This Creed has protected and shaped the life of the Church for centuries.[2] But while the Creed has protected the Church against Arius and Marcion, what is the role of the Creed in our own day?

D.H. Williams writes:

“Too many in Church leadership today seem to have forgotten that the building of a foundational Christian identity is based upon that which the church has received, preserved, and carefully transmitted to each generation of believers.”[3]

This is the role of the Creed: to pass the faith to each generation of believers.

I am sure you have heard, “I don’t like all these divisive doctrinal questions; my confession is No Creed, but Christ.” This statement is true: doctrine does divide, but if you were to ask “Would avoiding creeds and confessions liberate us from our problems and clear up all the confusion?” The irony of this situation is that if someone asked a “No Creed, but Christ” individual what he believes about Jesus, what would he say? The answer is that no matter what he says about Christ, he is already articulating a creed of his own.

If a Mormon comes to your doorstep and asks you if Jesus was truly God, however, you answer that question, you are articulating an orthodox or unorthodox creed. In other words, creeds are inescapable. The Creeds are quite offensive to the modern evangelical because it means they have to trust in others and not themselves. You have to trust in the faithfulness of your forefathers. It is a form of obedience to the fifth commandment. You must trust the faithfulness and wisdom of those before you. They have spent their theological journeys carefully working through these issues and refining them against heresies that arose in the early church. The Creeds call us to connect with our past and root ourselves in our family history.

The question the Creeds, particularly the Nicene Creed, seeks to answer is: what do you believe about Jesus? When it comes to the Creeds, you are always one iota away from heresy. This is why it is so important to think carefully about a Creed. Who will you trust: the brilliance of a recent Ph.D grad, a popular podcaster, or the consideration and study of the Councils?[4] Councils do err; they are not perfect, but one quick survey through the Nicene Creed will reveal rather quickly that every phrase of the Creed is an implicit or explicit biblical truth.

What is the purpose of a Creed?

The Creed protects us from error and guides us in truth. It is not an invention of man. The Jews had a creed. The first official creed of the Hebrew Scriptures is found in Deuteronomy 6:4: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one.” Creeds are declarations of what a people believe concerning the Scriptures. A Creed tells us what we should be willing to die for and what we should not be willing to die for.

Will I die for the divinity of the Son? Would I give my life to defend the incarnation of Jesus? These questions carry greater weight than the authorship of Hebrews or what eschatological view one upholds (pre-amil-postmil).

The Creeds help us differentiate whether things are of primary importance—issues where no compromise is acceptable—or if they are secondary issues—issues where legitimate debate can occur. But don’t the creeds lead to controversy and division? “Ironically, they are not the cause of doctrinal controversy; they are the answer to it.”[5]

The ancient creeds have liberated us from the frustrations of doctrinal controversy. They teach us that we do not have to reinvent the wheel; we can move on and think through other issues and distinct cultural and sociological heresies of the 21st century.

In summary, the Creed settles primary questions, while different traditions settle secondary questions. This is why we have catechisms and confessions like the Westminster Confession, Heidelberg Catechism, and the 39 Articles to guide us on polity, sacraments, and the nature of predestination.

What does this not mean?

Nevertheless, we should not confuse secondary issues with applications of primary issues. For instance, human sexuality is an extension of “God as Creator/Maker of Heaven and Earth.” God created them, male and female. A confusion of sexes would demonstrate a confusion of God as Creator.

So, the premises of the Creeds are not mere abstract doctrines but reach deeply into the fabric of civilization. Postmillennialism is not a necessary deduction of “He shall come again to judge the living and dead.” Other eschatological positions can also agree with that creedal statement. Still, the preservation of human sexuality is an application of the Creator theme at the beginning of the Nicene Creed. Therefore, we should not separate essential applications—like human sexuality—from the Creed based on their absence in the Creed. They are, in fact, applications of it and ought to be treated as primary issues or extensions/applications from the primary theses of the Creed.

A church can have strong positions on Christian education, eschatology, worship, sacraments, etc.. Still, the Creeds clearly state that our differences with other bodies over these secondary issues are not where we should divide in our Christian commitment. We can and should form warm fraternal relations with these traditions. The Creeds help us keep central things and apply those central elements to contemporary concerns. But it can also aid us in being open to discussing and interacting with other bodies that differ with us over genuine secondary issues.

What does this mean?

Ultimately, this means that we become dogmatic about the Christian faith to the point of death. This means that the Creeds should shape our catholicity. It should shape the way our children think about the world. They should not grow up with an isolationist mindset but rather a relatively broad view of the Christian world.

Practically, I have often encouraged people to visit different types of Protestant churches on vacation, whether a conservative Anglican or Lutheran Church or something of that nature, to expand their horizons.

A Note of Caution

Some new to the faith must mature into a particular theological tradition. Pastorally, someone new to the Reformed Faith should not read Karl Barth and Adolf von Harnack. He should read foundational books in the Reformed faith. Books by R.C. Sproul or Douglas Wilson are excellent foundational resources.

As a pastor, I don’t want my parishioners to be Reformed but one step from becoming an Anglican; instead, I want you to be deeply committed to our Reformational tradition and become conversant with different theological traditions. Maturity means knowing where you are, where you came from, and who is out there. This is precisely why the Creeds are so vital, because they give you boundaries. They tell you precisely where the dividing line is.

An Overview of the NICENE CREED

With that introduction in mind, let us now move into some of the pieces of The Nicene Creed. This Christian Statement defines precisely and thoroughly what we believe the Church has confessed and what has been of primary importance to the Church universal. We can talk about the Apostle’s Creed, but the Apostle’s Creed, though significant, is not as comprehensive, and historically has never been the central creed of the Church. On the other hand, the Nicene Creed is the most widely used Creed in the world.

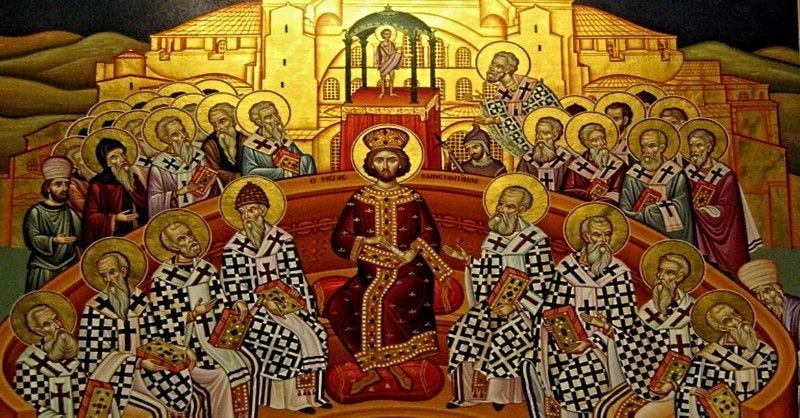

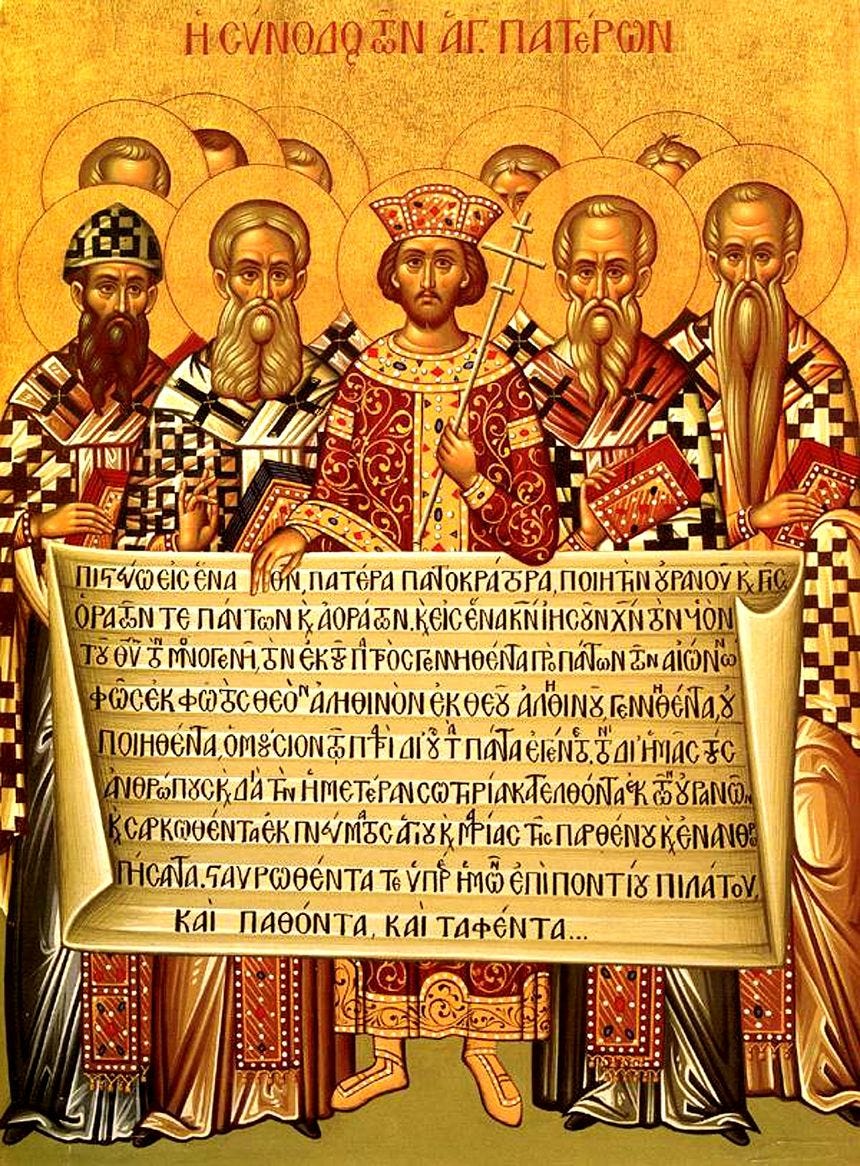

As I have mentioned earlier, the Creeds emerged due to fighting heresies. The Nicene Creed[6] resulted from the Council of Nicea in 325 AD.[7] The Council was convened because of the “prevailing questions concerning the nature of Jesus Christ and God the Father.”[8] Here are some general observations about the Creed:

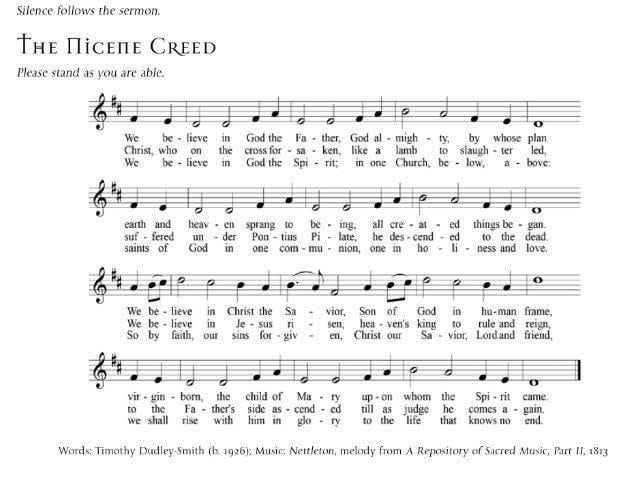

a) The first significant detail about the Nicene Creed is its first two words. The Creed begins with the words: “We believe.” The Nicene Creed is not a catechetical creed like the Apostle’s Creed; it is not meant to be memorized in a catechism class; it is meant as a tool to confess in corporate worship.

The Nicene Creed is the Creed of the Church. It is meant for the “we” of corporate worship (pisteuomen, “We Believe”). This is one reason it is the most widely used Creed in the Church. Whereas the Apostle’s Creed was not a Creed formulated by a council or a court, the Nicene Creed was formulated by courts and council as a response to heresies in the early church.[9] The Nicene Creed is not the expression of an individual but of the Church. In other words, you cannot confess this Creed apart from the Church because this is a “WE” Creed, not an “I” Creed.

b) The other point to observe is that the Nicene Creed does not separate the “We believe” from the “We Shall live.” In other words, this Creed calls us to worship the God revealed in the Scriptures. Athanasius once wrote that:

“Faith and godliness are connected and are sisters: he who believes in God is not cut off from godliness, and he who has godliness really believes.”[10]

This is not a mere intellectual creed that we put in our pockets and take out when we encounter a member of a cult. To declare that “we believe in One God, the Father Almighty,” means that we are also trusting in the One God, the Father Almighty. We are trusting that He will be a mighty God for us. In other words, to believe is to trust and to trust is to believe.[11] L. Charles Jackson wrote: “Just as the Son is inseparable from the Father, so faith cannot be separated from godly living.”[12] To summarize this section, let me quote T.F. Torrance, who wrote:

“An outstanding mark of the Nicene approach was its association of faith and…godliness, that is with a mode of worship, behavior and thought that was devout and worthy of God and the Son and the Holy Spirit.”[13]

c) The other fascinating detail about the Nicene Creed is that it is a beautiful narrative that flows brilliantly from beginning to end. It begins with Creation: He is maker of heaven and Earth and it ends in Consummation: We look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. When we confess the Nicene Creed we are confessing the story of redemption; we are confessing the story that the Church has fought for and died for and lived for in the last two thousand years.

We are confessing the historicity of Genesis through Revelation, that all that is written is true and right and to be loved. When we confess this Creed together, we are confessing our people’s history, our Lord’s life, and our life. We are confessing that we are a part of all those events. Why did Jesus come down from heaven? The Nicene Creed teaches us that He came down to obey His Father but also came for US and OUR Salvation. You see, this Creed is about us and our salvation. It anchors us in redemption and it anchors us in God’s story.

d) The other unique element of the Nicene Creed is found in the penultimate sentence: “We believe in one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church.” When we think of our confession when we think about what it means to be a Christian, we may think of the Trinity, the Virgin Birth, or the Death and Resurrection of our Lord, but I would say that very few in this country would add a belief in the Church as “part of their gospel confession.”[14] Most people would say they believe in it but that it is not vital to their confession. Some would say: “Of course, the Church is important, but it is not central.”[15] It is hard, then, to imagine the average American confessing to the Church as part of their life-and-death creed. What did our Ancient Fathers and our Reformation forefathers say about the Church? They said, “Apart from the Church, there is no ordinary possibility of salvation.” Is it possible for someone to be saved on their deathbed or in some remote location where gathering for worship is not possible? Yes. But this has never been the ordinary way people come into a true and lasting relationship with Christ. The Westminster Confession of Faith, echoing the Nicene Creed, says in Chapter 25:

“…the Church which is also catholic or universal under the Gospel (not confined to one nation, as before under the law), consists of all those throughout the world that profess the true religion; and of their children: and is the kingdom of the Lord Jesus Christ, the house and family of God, out of which there is no ordinary possibility of salvation.”

God has ordained that His bride be the ordinary way for salvation to come to the world. This is why Paul says in Ephesians 3 that through the Church, God's manifold wisdom will be made known.

Some years ago, George Barna wrote a book urging Christians to find a vibrant faith outside the Church. He writes in his book, “…believers should choose from a proliferation of options, weaving together a set of favored alternatives into a unique tapestry that constitutes the personal 'church' of the individual."[16] George Barna says that this would be a true revolution. One writer responded,

“Do you want to become a Revolutionary? First, trade your copy of Revolution for Life Together,[17] the manifesto written by Dietrich Bonhoeffer during the dark days of Nazi Germany; Then, if you want to do heroic and revolutionary exploits, go back to your local church. That's something so spiritually challenging that several million people no longer want to do it.”[18]

Conclusion

To be Creedal means to be one with the people of God, one in faith, one in baptism, and one in submission to the Lord. The Nicene Creed brings all these themes together. It is a Creed to be confessed and loved by the Church. It is not some ethereal set of propositions; it is a rich display of biblical theology encompassing all of redemptive history.

Furthermore, it is not divorced from contemporary concerns. God as Creator means God is deeply invested in his creation. He is engaged in the creation process and forms his creation after his image without confusion.

While some may attempt to find solace in a vision of the Church that is separate from the holy, catholic, and apostolic faith, the Nicene Creed grounds us in the living faith of our fathers. To deny it is not to be free from the Creed but to formulate your own. Acting as a creative artist and reinventing the Creed endangers your soul. Every faithful church is a creedal church. Believe it. Recite it. Sing it. Embrace it for your sake and those you love.

[1] The word attempts to explain the relationship of the Holy Spirit to the other two persons of the Trinity. Does the Holy Spirit proceed from the Father, the Son or both? John 15:26-27. The word filioque means “and the son.”

[2] L. Charles Jackson, Faith of Our Fathers: A Study of the Nicene Creed. This lesson is primarily based on L. Charles Jackson’s work. References and quotes will come mainly from his book.

[3] Quoted in Jackson’s Faith of Our Fathers.

[4] Of course, I stress that councils do err.

[5] Charles Jackson, pg. 4.

[6] See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicene_Creed for the distinction between Constantinople (381) and Nicea (325).

[7] At that time, the text ended after the words "We believe in the Holy Spirit"” after with an anathema was added

[8] Charles Jackson, 8.

[9] These same heresies are still widespread today, except using different titles.

[10] Jackson, 15.

[11] See Jackson, 16.

[12] Ibid. 17

[13] Ibid. 17

[14] Jackson.

[15] Jackson. 105.

[16] Quoted in CT http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2006/january/13.69.html?start=2

[17] Bonhoeffer writes: “Let him who cannot be alone beware of community. . . Let him who is not in community beware of being alone” (p. 77).”

[18] Ibid.

Having only about five years in the Reformed traditions, this is very helpful. Appreciation of the History of the Church and the men of God who are such pillars upon the foundation of Christ is an incalculable step in the right direction.